Distance Learning Module: Observational Data/Night Sky Journal

Hone your hands-on science skills by recording observation-based astronomical data from your own home!

For the next month, keep a journal of fieldnotes to record ongoing observational data about the night sky.

BEFORE YOU BEGIN

Terms to Understand:

observational study: a systematic way to collect data by observing the subject matter in question (in contrast with an experimental study, in which the researcher actively manipulates a variable and analyzes the results using the scientific method)

longitudinal study: a type of research comprising repeated observations of the same variables over short or long periods of time

Reflect and Discuss:

Why is observation the most appropriate design for this particular study? What sorts of experimental studies might be performed on Earth that could help us understand the extraterrestrial environment?

What will you choose to record? You will help maintain the validity of your observations by recording the same data on a repeating basis. Make your observations at the same time (or times) each night, and from the same location (or set of locations).

Note:

For your safety, make sure to secure an adult’s permission before leaving the home at night. Better yet: work outside as a family, and compare everyone’s notes/sketches at the end of the evening!

HOW IT WORKS

Fieldnotes generally consist of two parts:

Descriptive information, in which you attempt to accurately document factual data [e.g., date and time] and the settings that you observe

Reflective information, in which you record your thoughts, ideas, questions, and concerns as you are conducting the observation.

Field notes should be fleshed out as soon as possible after an observation is completed. Your initial notes may be recorded in cryptic form and, unless additional detail is added as soon as possible after the observation, important facts and opportunities for fully interpreting the data may be lost.

A thorough collection of observations should include:

Date, time, and location of each observation made

Description of weather conditions (wind, cloud cover, precipitation), including temperature and air pressure (can obtain these from the local weather service if you do not have access to an outdoor thermometer/barometer

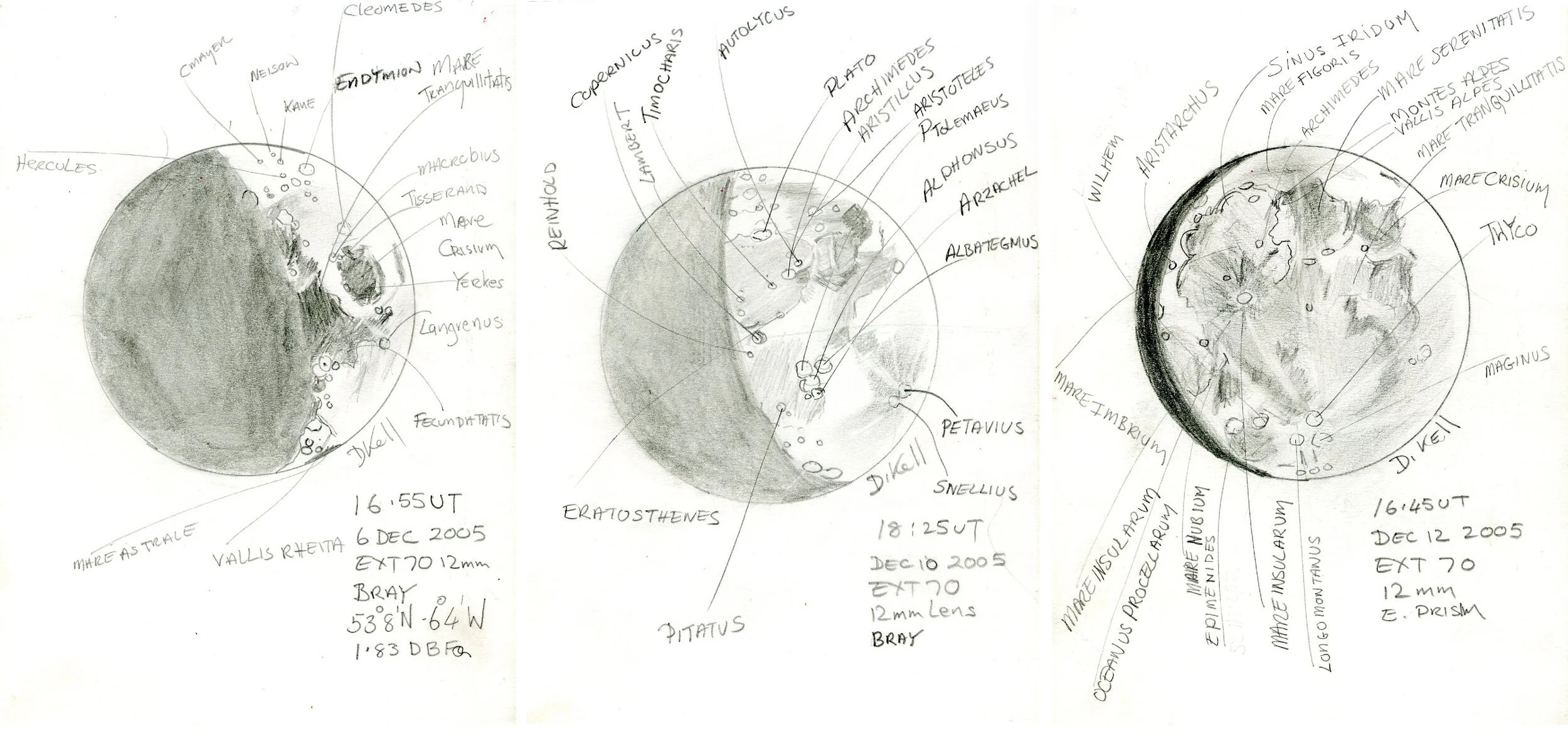

Presence/absence, phase, and approximate direction and location (altitude) of moon

If the moon is visible at the time of your viewing, sketch what you see, focusing on the angle and percent visible. Keep in mind that the moon “gets light from the right,” meaning that the lit portion of the moon progresses from right to left across the moon going from new moon to full moon.

Use sketches to record the presence of visible planets, constellations and/or asterisms in your field of view

constellation: a group of stars forming a recognizable pattern when viewed from Earth, which is traditionally identified with a mythological figure; their boundaries are designated by the International Astronomical Union. Examples: Cassiopeia (the queen), Ursa Major (the great bear)

asterism: smaller groups of stars, also visible to the naked eye, which do not form constellations on their own. Example: the Big Dipper, which is one part of the constellation Ursa Major

Experiment with sketching large portions of the sky, versus focusing on one object (e.g. the Moon, a constellation). All sketches should note which direction you were looking at the time of the sketch. If focusing on one celestial object, note the presence of other nearby objects (e.g. the Moon, Venus) in your field of vision that may serve as reference points.

METHODOLOGY

Choose a notebook to record your observations. Think about what characteristics will be most convenient for indoor/outdoor use—do you prefer a spiral binding for easy page turning? Blank pages for uninterrupted sketches? A hard cover for a built-in solid writing surface?

Before you begin, make a written list of all the data points that you will record. Follow the list to keep your observations consistent for the duration of the study.

Gather supplies for your outdoor observation period. Be sure to include flashlight(s), weather-appropriate dress and gear, writing implement(s), and your journal. For your safety, do not work outside at night without your parent or guardian’s permission. Stay in familiar areas only.

Do what you can to reduce light pollution in your observation location—for example, turn off porch/garage lights and use drapes to keep light indoors. Make your observations from the same location every night.

Record your nightly observations, working through your list one item at a time.

Tips for observational research:

Be accurate. You only get one chance to observe a particular moment in time, so accuracy counts! Fortunately, observation is a skill, like any, that improves with practice. Each set of observations is a new opportunity to improve your noticing and note-taking skills and develop your own style of transcribing observations.

Be descriptive. Use descriptive words to document what you observe, so that you don't end up making assumptions about what you meant when you review the notes later. This is where sketches become very useful.

Record insights and thoughts. As you observe, be thinking about the underlying meaning of what you observe and record your thoughts and ideas accordingly. This will help when you return to the journal later to record your reflective information.

ANALYZING YOUR DATA

Compare your observations to the current Sky Report from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA):

Reflect and Discuss:

What patterns do you notice? What parts of the sky look the same every night? What changes from night to night?

What factors in your local environment affected your ability to make astronomical observations? In what ways?

What would you expect to see if you took the same observations for another month, from a different location? From the same location, but at different times of night? Try it!

Has nightly observation helped you learn to find/identify any new celestial objects? Which ones?

Did you make any reservations to your list of required data after one or two rounds of observations? What worked and didn’t work in practice, versus what you’d expected before being in the field?

What are the limits to this type of study, versus an experimental study? What could an experiment tell us that observations cannot?

How about the benefits—what can you learn from observation that you cannot achieve via experimentation?

What are some ways that you might apply your skills of observation and data recording to other branches of science (e.g. biology)?