At-Home STEM Activity: Create Your Own Impact Crater

Today we will show you how to create an impact crater using simple kitchen ingredients, but first, let's find out more about them.

Tycho, an impact crater located in the southern lunar highlands on the moon (Image credit: NASA / Wikimedia Commons)

In a previous blog post this week, we talked about the different space objects such as meteoroids that exist in our solar system and beyond. Take a look at that post if you haven’t already, since they play an important part in the formation of craters.

What is an impact crater?

When a meteoroid is able to penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere without completely breaking apart, it is called a meteor. When a meteor hits the Earth’s surface it is called a meteorite. A meteorite travels at very high speeds, ranging from 25,000 to 160,000 miles per hour (40,233 - 257,495 kilometers per hour). When it hits the ground at such a high speed, a bowl-shaped depression, or hole called a crater is produced.

An aerial view of the 50,000 year old Barringer Crater, also known as Meteor Crater located in Coconino County, Arizona, USA. The crater is about 3,900 feet (1,200 meters) in diameter (Image credit: Shane.torgerson / Wikimedia Commons)

Often called impact craters, these depressions caused by meteorites are a common feature on many planet and moon surfaces, including Earth. Click here to view a world map of crater locations. You can hover over the map with your cursor to learn more about each crater.

Crater Features

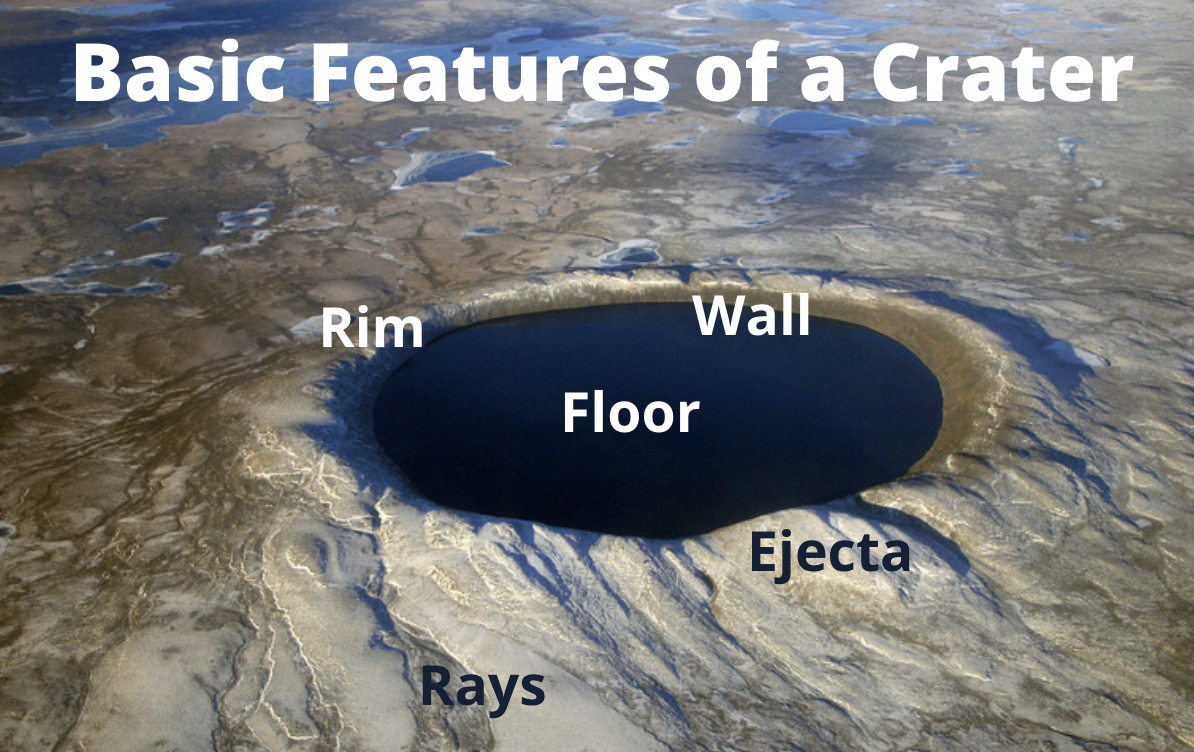

Craters are a circular shape and have several parts to them:

Floor

The floor is the bottom of the crater, and it is usually below the level of the surrounding ground. Some large craters (greater than 18 miles/30 kilometers) possess a central peak in the center of the floor. The peak is caused by the crater collapsing on itself and when the rock beneath the crater rebounds, or bounces back up.

Walls

The steep sides of the crater are called the walls. They often have stair-like terraces caused by parts of the walls slumping due to gravity.

Rim

The rim is the edge of the crater and it is usually slightly higher than the surrounding ground due to material being pushed up when the crater was formed.

Ejecta

Ejecta is the rock material that was thrown out of the area during the impact. It usually surrounds the crater’s rim as well as the ground close to the crater.

Rays

Ejecta material can often spray in all directions, sometimes for great distances producing bright streaks called rays.

Locations of crater features are shown on top of the 1.4 million-year-old Pingualuit Crater in Nunavik, northern Quebec, Canada. This crater is 2.14 miles (3.44 kilometers) in diameter and is home to the 876-foot deep Lake Pingualuk (Image credit: NASA. Courtesy of Denis Sarrazin / Wikimedia Commons)

Create Your Own Impact Crater

Now that you have some background information about impact craters and how they are formed, you can simulate your own crater impact with simple kitchen ingredients.

Below are the list of ingredients you’ll need and the step-by-step instructions to follow.

Materials

Cake pan (round or rectangle)

Flour

Cake sprinkles

Cocoa powder or cinnamon (or some other ingredient that’s a different color than the flour and sprinkles). Using different colors and textures will help you see the results of the experiment more clearly

Spoon or sifter

2 or 3 small rocks of different sizes to use as your meteorites

Instructions

First, take your cake pan and spread about an inch of flour all over the bottom

Next, add a thin layer of cake sprinkles on top of the flour

Then, sift your cocoa or cinnamon in a thin layer so that the sprinkles and flour are covered

Finally, you’re ready to simulate a meteorite hitting the Earth’s surface. Hold one of the rocks above your head and drop it into the cake pan.

Observe the ejecta pattern that was created. Try dropping different sized rocks at different heights and angles to see how the ejecta pattern differs from each “meteorite impact”.

Check out this video to see how NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at CalTech created this experiment.

By Megan Goldsmith